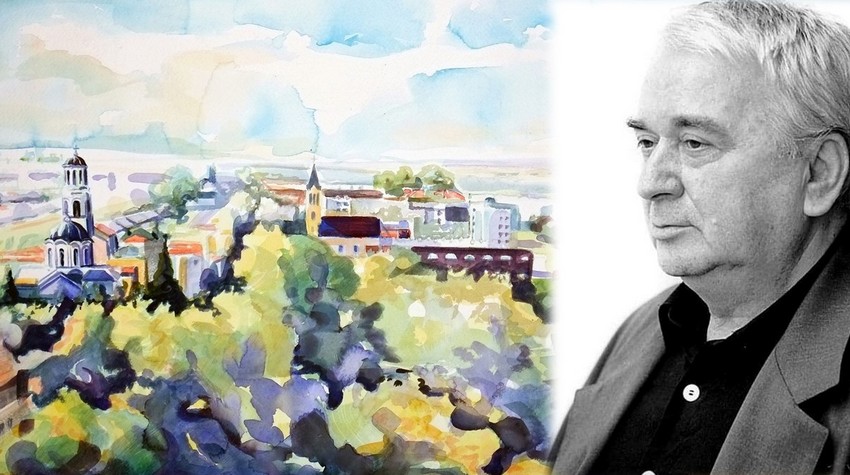

MARKO RADIĆ: VIŠEGRAD IS ANYTHING BUT ORDINARY

Marko Radić, former Director of the Trebinje Tourist Organization and current Head of the Tourism Promotion Department at the Tourist Organization of Republika Srpska, frequently shares his views on domestic tourism through his blog and social media channels.

In recent days, Radić published a compelling author’s text on his blog titled “Višegrad, Between Stone and Words”, written while working on the Tourism Development Strategy of the Municipality of Višegrad.

In the

text, Radić reflects on the deeper meaning of destination branding, emphasizing

that Višegrad cannot be reduced to numbers, capacities, and infrastructure

alone.

“Višegrad

has weight. Višegrad is anything but ordinary,” Radić writes, explaining that

strategic tourism planning inevitably leads beyond statistics and into the

realm of emotion, memory, and identity.

Revisiting

Ivo Andrić’s novel “The Bridge on the Drina” for the first time since high

school, Radić notes that the Nobel laureate unintentionally authored the most

important branding guide Višegrad could ever have. What was once an obligation

for students, he now reads as a tourism professional, understanding that a

destination must also be an emotion.

According

to Radić, the Mehmed Paša Sokolović Bridge is far more than a photogenic

landmark. It is a symbol of endurance, a testament to how one individual’s

creation can outlive politics, borders, and time. Its UNESCO World Heritage

status, which is approaching two decades, represents not only recognition, but

also responsibility — an obligation to convey stories of encounters, suffering,

hope, and continuity.

Radić also points out that Višegrad’s greatest strength lies in its universal story, amplified by the fact that the region produced a Nobel Prize winner. Andrić, he argues, translated the complex local history of the Drina region into a language the world can understand.

“When

foreigners arrive in Višegrad, they seek to feel the universality of a small

place and a great story,” Radić writes, describing this as the essence of

modern tourism storytelling. He emphasizes that Andrić left behind a “gold

mine” of narratives, waiting to be presented in a way today’s visitors can

connect with.

Walking

through Višegrad, Radić observes layers of history that may appear conflicting,

but together form a complete tourism offer — from Andrić’s modest childhood

home and classroom, to the emerald-green Drina River, and finally Andrićgrad,

the vision of filmmaker Emir Kusturica. While critics often argue that

Andrićgrad commercializes myth, visitors, Radić notes, find experience and

content.

“Višegrad

will not comfort you with a simple story,” he concludes. “It offers the bridge

as authenticity and Andrićgrad as content. This fusion of old and new, silence

and vibrancy, is what makes the destination alive.”

Radić

stresses that tourism should not sell sterile beauty, but authenticity, depth,

and emotion. A tourism strategy, he argues, cannot focus solely on beds and

roads — it must return to understanding.

The

true task, Radić writes, is to bring visitors to the bridge not for a selfie,

but so they can feel what Andrić once described as “life being an

incomprehensible miracle that constantly fades and disperses, yet endures and

stands firm, like the bridge on the Drina.”

“That,”

Radić concludes, “is the value Višegrad has. And that is the value we must

offer to the world we wish to welcome.”