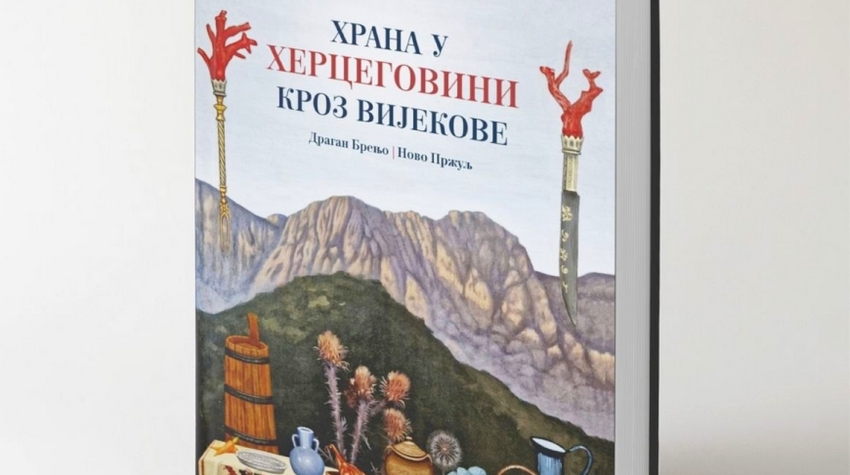

WHAT DID HERZEGOVINIANS EAT THROUGH THE CENTURIES?

In an interview with Euronews, Dragan Brenjo, one of the authors of the monograph "Food in Herzegovina Through the Centuries", discussed the eating habits, customs, and food history of this unique region.

In

Herzegovina, food has never been just a daily necessity – throughout the

centuries, it has served as a reflection of culture, social class, and

historical context. This is precisely what the monograph "Food in

Herzegovina Through the Centuries", co-authored by Dr. Dragan Brenjo and

academician Nova Pržulj, seeks to explore. The book acts as a culinary

chronicle of the region’s diet over the past 800 years.

“It

all began during the commemoration of 800 years of the Eparchy of

Zahumlje-Herzegovina and the Littoral. Mostar parish priest Radivoje Krulj

suggested we focus on food, and the blessing of the late Bishop Atanasije gave

the project a special weight and responsibility,” recalls Dr. Brenjo for

Euronews.ba.

The

book aims to present food not merely as a culinary phenomenon but as part of a

complex cultural system. “Diet was directly influenced by social structures and

class divisions — the menus of the nobility, clergy, peasants, and soldiers

never overlapped, but they did influence each other,” the author explains.

According to Brenjo, many dietary customs trace their roots back to the late Middle Ages. Later influences — from the Ottoman conquests and Columbus’s discoveries to Germanic and Austro-Hungarian cuisine — only enriched this medieval foundation.

The

main ingredients in the Herzegovinian diet were grains — millet, barley, wheat,

rye, and oats. “Millet and barley were consumed as porridge or bread. Common

vegetables included onions (both black and white), cabbage, turnips, lentils,

and broad beans. Meat was rare and usually reserved for special occasions, with

lamb being the most common. Pork was less frequent, and beef was virtually

unknown. Wild game was rarely eaten, while fish was relatively common,”

explains Brenjo.

Among

the most fascinating aspects of the book are recipes such as “kneževa

jagnjetina u mlijeku” — lamb in milk, a favorite dish of the 12th-century Hum

prince Miroslav — or chicken in sauce from the same era. The book also features

a description of 15th-century cutlery belonging to Stefan Vukčić Kosača: forks

made of silver, coral, and rock crystal.

“People

today don’t think about food the way our ancestors did. For them, food was

often divine — it meant life and survival. That sense of wonder is woven into

our tradition and DNA, especially in Herzegovina,” says Dr. Brenjo.

He adds that during times of hunger, people approached food with gratitude and reverence, unlike today’s culture of abundance.

The

geographical and climatic features of Herzegovina — with its karst fields and

highlands — significantly shaped its agriculture and nutrition.

“Herzegovina

is a land of stone. Traditional stone houses, built since the Middle Ages,

confirm the strength of local identity. In remote villages, these houses are

still built today according to ancient customs,” the author notes.

The

monograph concludes with an intriguing look at phrases and idioms related to

food, especially bread, which in local speech symbolizes life and existence.

“Through

language, we can clearly see how deeply food is rooted in the collective

consciousness of the people,” Dr. Brenjo concludes.