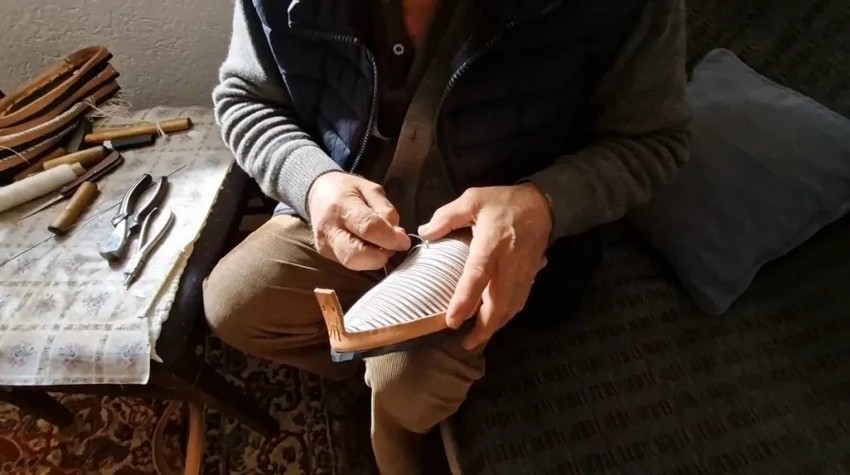

TRADITIONAL HERZEGOVINIAN SHOES MADE BY SLOBODAN POPOVIĆ TRAVEL THE GLOBE

Slobodan Popović from Ljubinje is the last known traditional shoemaker (opančar) in Herzegovina—a humble and patient craftsman who has, almost by chance, revived a centuries-old trade.

“I’m

not completely sure I’m the only one, but I believe I am. I get orders from

both East and West Herzegovina, and all my customers tell me there’s no one

else doing this,” says Popović, whose calm nature reflects the dedication and

precision required for his craft.

Despite

approaching his ninth decade, Popović only began making traditional shoes, or

"opanci", during the war in the 1990s. “I was stationed at a

relatively calm frontline, and while we had clothes, footwear was falling

apart. There was no money and no stores. So I gathered some makeshift materials

and made my first pair of opanci. They were clumsy, but they did the job.

Others around me were also barefoot, so I kept making more. Each new pair got

better.”

After

the war, his name quickly spread. Today, his handmade shoes are worn by

cultural folk groups across Bosnia and Herzegovina—in Sarajevo, Ilijaš, and

Bijeljina—and have even been sent to Rab Island in Croatia and to Serbian

diaspora communities in places like Gajdobra, Serbia. He recalls a single order

of 50 pairs from Rab, and now believes his opanci have reached every continent

except Africa.

“Nowadays,

orders come smoothly—people hear about me, find me on Facebook, and place their

orders,” he says. As business grew, Popović invested in molds ranging from baby

sizes to size 51, which he once made for a basketball player from Gacko playing

in Belgrade.

The real challenge, he explains, is not crafting the shoes, but sourcing the materials. “When I was young, most of the materials—except for the metal buckles—were readily available at home. Now I source leather from Belgrade, rubber from Sarajevo, buckles from Novi Sad, and twine from Dubrovnik,” he says.

Most

materials arrive quickly via express shipping, which increases the final cost.

Still, his prices remain accessible: until recently, a pair cost 100 KM (about

€50), and now ranges from 120 to 130 KM, depending on the model.

“When

I work alone, it takes me two days to make one pair. Sometimes my wife or one

of my sons helps, especially if the customer is in a hurry,” says Popović. “I

don’t make a huge profit, but it’s a nice supplement to my pension. If I

focused solely on the business and did more promotion, it could be a full-time

income. But I treat it as a hobby, so any money I earn feels like a bonus. And

I can’t complain—my customers are generous and never try to haggle.”

He is

especially proud that both of his sons have shown interest in the trade. “It’s

good for them to learn a craft, and it means the tradition of opančarstvo might

continue in Herzegovina,” Popović concludes.